Many years ago, I got a letter from a woman who relayed the following story to me. She used medication for hypertension and had recently gotten a deep-tissue massage. At the spa, they told her to wait and drink water after her session, but she was in a hurry. She went right to her car, backed out of her parking space, blacked out, and then crashed the car. (No one was hurt, thankfully.) She asked if I could provide any data about how massage might have caused this to happen so the DMV wouldn’t take away her driver’s license. I found some studies about massage and blood pressure, but I never heard back from her, so I don’t know how it all worked out.

What happened here? Was it the hypertension? The medications? The deep-tissue massage? The timing? Or a combination of everything?

People faint, a lot. About 3 percent of all ER visits and 6 percent of hospital admissions are due to syncopal events, and they cost about $2 billion a year to treat.

But fainting is not a disease. Rather, it’s a symptom of a problem with maintaining a stable internal environment. Massage therapy also challenges the internal environment, through our influence on sympathetic/parasympathetic states, blood flow, skin temperature, hormone secretions, and more. In this article, we will look at the interface between massage therapy and the homeostatic challenges that might lead to a feeling of faintness or a complete loss of consciousness.

What Is Fainting?

A synonym for fainting is the term syncope, which translates to “whole” and “cut off.” In other words, a complete and sudden loss of consciousness. It’s important to distinguish between fainting and feeling faint: Dizziness, light-headedness, and nausea often precede a syncopal event, or they can be related to other issues altogether. So, while these two phenomena may be connected, it’s often not a direct progression from feeling faint to passing out.

What Happens?

The active functional cells of any given organ are called the parenchymal cells. The parenchymal cells of the brain run mainly on sugar. Unlike some other organs, if the brain runs out of sugar, it has no backup systems to provide fuel. For this reason, if the brain has inadequate access, even for just a few seconds, it may temporarily cease to function.

Why would the nutrient flow to the brain be interrupted? It’s often a problem with keeping blood pressure appropriately high; this is frequently related to some form of dysautonomia or cardiac dysfunction, or both. Ultimately, a syncopal event is linked to anything that causes the arteries going to the head to suddenly dilate and drop blood pressure.

Types of Fainting

Experts categorize fainting into several categories, usually related to precipitating factors. However, many syncopal episodes are multifactorial, involving many simultaneous triggers, so there can be substantial overlap. Here’s a short list of types of nonemergency fainting that massage therapists may encounter.

Vasovagal Syncope

Remember that the vagus nerve is the main agent of parasympathetic response. When it’s stimulated, especially in a sudden way, it can cause an abrupt drop in blood pressure and heart rate that can cause fainting. What might stimulate the vagus nerve? A strong emotional response, internal straining (i.e., a bowel movement, sneeze, gagging, or coughing), and many other factors, including something like painful massage, especially in the abdomen.

Orthostatic Intolerance

This is an umbrella term for a general inability to maintain appropriate blood pressure to the head in relationship to gravity. It may involve problems in the feedback loop between the brain and the heart/arteries. Factors include bed rest, medications for hypertension or heart function, low muscle tone, and others. A person with any type of orthostatic intolerance won’t do well with rapid changes in position, especially coming from lying down to sitting or from sitting to standing—relevant for massage therapists, of course!

Orthostatic intolerance has three main subtypes that show different patterns: orthostatic hypotension, neurally mediated hypotension, and postural orthostatic tachycardia syndrome (POTS). Of these, only POTS involves an elevated heart rate. Interestingly, people with POTS don’t usually fully lose consciousness, although symptoms of faintness along with a rapid heart rate are very frequent.

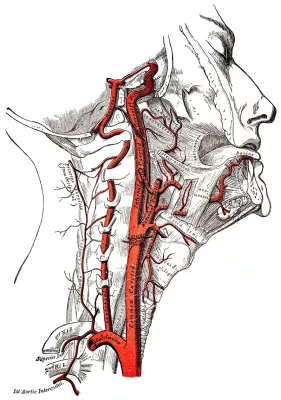

Carotid Sinus Reflex

The carotid sinus is a wide spot in the left and right carotid arteries where they split into anterior and posterior branches on their way up into the cranium. This area is highly innervated with sensory receptors, and any direct pressure can cause a rapid drop in blood pressure to the head, leading to fainting. This can be an issue in the context of poorly placed chair massage cushions, as we will see.

Metabolic Causes

Low blood sugar (which can be exacerbated by massage), severe anemia, hyperventilation, overheating, and dehydration are metabolic factors that can increase the risk of fainting.

Other Types

Fainting may also involve drug side effects, complex medical problems with the heart, seizures, severe forms of dysautonomia, blood loss, and other issues.

Complications

Typical fainting episodes are short and not serious. However, they carry a risk of falls and head injuries. This is particularly dangerous among elderly people—which is also the population most at risk for fainting. In addition, a tendency to faint can make it unsafe for a person to drive or operate heavy machinery. And of course, a person with repeating syncopal episodes needs medical attention to determine whether the cause is threatening and/or treatable.

Signs and Symptoms

“Feeling faint” is a label given to a wide variety of symptoms, including dizziness, vertigo, light-headedness, nausea, sensory changes (numbness, tingling, flashing lights, or tinnitus), sweating, shortness of breath, mental fogginess, and overwhelming weakness. Collectively, these symptoms are sometimes called presyncope, and they indicate that a person may be about to lose consciousness.

However, feeling faint and fainting are two different things. Many conditions involve presyncope symptoms without a full loss of consciousness. It’s useful for massage therapists to make this distinction, because feeling faint after a table massage isn’t uncommon, but actual fainting is—and of course we need to be prepared to respond to these situations differently.

What to Do

If a person faints at some point during a massage therapy session, everything needs to stop. Depending on how long they lose consciousness, whether they are fully coherent when they wake up, and many other factors, it may be necessary to call for emergency services or at least the client’s emergency contact to make sure they get home safely.

If a person experiences presyncope symptoms during a massage appointment, then it’s necessary to make sure they’re lying down to restore blood flow to the head until they feel stabilized.

Red flags for fainting and near-fainting episodes include chest pain, shortness of breath, palpitations, loss of words, persistent weakness, and changes in mentation. These are all good reasons to call emergency services immediately.

More details on risk factors, what to do if a person has a presyncope or fainting episode, and when to call 911 are provided in the video that accompanies this article.

Implications for Massage

Fainting with Chair Massage

The most likely setting in which a massage therapist might have a client who completely loses consciousness is in the context of chair massage. Syncope during or immediately after a chair massage is not uncommon. Opinions about why this happens as often as it does vary. Some experts point to dehydration and low blood sugar. Another factor is misplacement of the cushions so that as the client relaxes into the chair, they get direct pressure at the carotid sinuses. This was the conclusion of Eric Brown, director of Massage Mastery Online. In his training program, when corrections were made in the placement of the face cradle, chair massage fainting episodes almost entirely ceased. The following is an excerpt from Brown’s training program:

“During an open house for the school, I was teaching the group a few techniques so they could get a sense of how chair massage worked. I passed one woman who lifted her face out of the face cradle. She looked at me as I walked by and said, ‘It’s hot in here.’ As I looked at her and gave an acknowledging nod, her eyes rolled into the back of her head, and she began shaking uncontrollably. I immediately asked her husband, who was massaging her, if she had a history of seizures as I reached to stop her from falling out of the chair.

“It wasn’t a seizure. She had simply fainted.

“She came to consciousness relatively quickly and ended up continuing with our mini workshop. She and her husband even enrolled in the professional training program.

“That was my first experience with someone fainting in the chair, but it certainly wasn’t my last. We experienced a series of fainting episodes—perhaps up to 10 occurrences within the first year of starting the training program.”—Eric Brown

When his program made corrections in the placement of the face cradle, chair massage fainting episodes ceased almost entirely.

Feeling Faint with Table Massage

Most massage therapists will probably never have a client faint while on the table, mainly because many of the most common triggers, like carotid sinus pressure, standing too long, emotional or physical stress, and straining, don’t happen in this context.

However, feeling dizzy, nauseated, or light-headed—that is, having presyncope symptoms—directly after a massage happens often, for many reasons. Low blood sugar, an unexpected reaction to a medication (which was the most likely cause for the person described at the beginning of this article), orthostatic intolerance, and even just the act of coming upright after being horizontal for an hour or more may trigger some uncomfortable and inefficient neurological and vascular adjustments.

This rarely leads to a complete loss of consciousness, but it can be scary. For clients who are at risk for this kind of reaction, it is a good idea to finish the massage with invigorating strokes, to encourage them to sequentially squeeze and release the muscles in their legs and arms to re-establish blood flow, and to stay with them as they come to a seated position—just to offer whatever external support they may need. If the feeling doesn’t stop within a few moments, especially if it is a repeating pattern, this is something they should pursue with their physician.

Resources

Brown, E. Massage Mastery Online. “The Fainting Phenomenon.” Accessed May 21, 2025. https://massagemastery.online/topic/the-fainting-phenomenon.

Cleveland Clinic. “Syncope (Fainting).” Last modified June 4, 2025. https://my.clevelandclinic.org/health/symptoms/21699-fainting.

Cutler, N. Institute for Integrative Health. “Be Prepared: What to Do When a Client Faints.” Accessed May 20, 2025. www.integrativehealthcare.org/mt/fainting-during-after-massage.

DePace, N., and M. E. Goldis. Franklin Cardiovascular Associates. “Cracking the Code of Dysautonomia: POTS, Orthostatic Hypotension, and Heart Health.” March 3, 2023. https://franklincardiovascular.com/dysautonomia-pots-and-orthostatic-hypotension.

Jeanmonod, R., D. Sahni, and M. Silberman. Vasovagal Episode. StatPearls Publishing, 2025. www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK470277.

MD Searchlight. “Vasovagal Episode.” Accessed May 2025. https://mdsearchlight.com/heart-health/vasovagal-episode.

Morag, R. Medscape. “Syncope.” Last modified September 11, 2024. https://emedicine.medscape.com/article/811669-overview.

Palmer, D. MassageTherapy.com. “Fainting and Chair Massage.” Accessed May 20, 2025. www.massagetherapy.com/articles/fainting-and-chair-massage.

Powell Key, A. WebMD. “Understanding Fainting: The Basics.” July 10, 2024. www.webmd.com/brain/understanding-fainting-basics.

Valenza, G., Z. Matić, and V. Catrambone. “The Brain–Heart Axis: Integrative Cooperation of Neural, Mechanical and Biochemical Pathways.” Nature Reviews Cardiology 22 (2025): 537–50. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41569-025-01140-3.

Waise, T. M. Z., H. J. Dranse, and T. K. T. Lam. “The Metabolic Role of Vagal Afferent Innervation.” Nature Reviews Gastroenterology & Hepatology 15 (2018): 625–36. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41575-018-0062-1.