It used to be believed that the uterus of someone who was not pregnant could move around inside the body. In Plato’s work, Timaeus, the empty womb is described as a wild animal, searching for purpose and wreaking havoc on a person’s health in the process. Other early writers suggested that if a womb was not held down by a growing fetus, it migrated and interfered with other organs, even into the neck, where it might cause death by choking. This phenomenon was known as the “wandering womb.”

It is worth noting that these early contributions to the study of uterine health were accepted without the benefit of direct observation, and the notion of ambulatory uteri was discarded when dissection was adopted to learn about the body. Eventually, in an updated attempt to explain uterine health problems, Galen suggested that “suffocation of the uterus” (also called hysterical apnea) was caused by retained menses that were trapped by semen and blood clots—not by a uterus that got up and went for a stroll to visit the spleen.

Truthfully, Plato and Galen and the others may have been onto something in terms of how the uterus and menses might impact a person’s health. In this discussion, we will see that the uterus itself doesn’t wander, but its contents sometimes do—and that can lead to big problems.

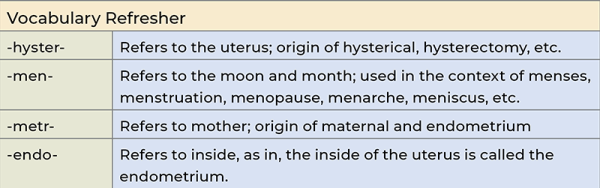

What Is Endometriosis?

Endo-metri-osis, literally “inside-uterus-condition” describes a situation in which the cells from the endometrium—the lining of the uterus that builds up each month in preparation for a possible pregnancy—become established in colonies in the pelvic region or abdominal cavity. This usually happens on top of nearby organs: the outer surface of the uterus, on the uterine tubes, the ovaries, bladder, colon, or other spaces in the peritoneum and the peritoneal wall. More rarely, colonies of endometrial cells have been found on the liver, in the lungs, and in the central nervous system. This is the closest thing we have to a “wandering womb.”

It’s hard to estimate how common endometriosis (sometimes called endo) is, because it can’t be officially diagnosed without an invasive procedure: a laparoscopic biopsy, where a small incision allows a camera to enter the pelvic cavity and take samples to look for signs of endometrial growths. Estimates suggest endo affects about 11 percent of people assigned female at birth, which amounts to about 6.5 million people of reproductive age in the US.

Pathophysiology

References to painful menstrual periods and uterine problems go back for centuries, but the modern understanding of endometriosis dates to 1921, when an American gynecologist named John A. Sampson noticed growths in the pelvic cavities of women undergoing surgery. His theory was that the growths formed from bits of the endometrium getting into the peritoneum via retrograde backflow. In other words, cells traveled up the uterine tubes (also called fallopian tubes) to be released from the fimbriae into the pelvic cavity.

Today, 104 years later, this is still the leading theory about how endometriosis develops, though it’s clear that many other dynamics must also be at work. We know that many people assigned female at birth have endometrial cells in their peritoneal fluid, especially during menstruation, but not all of them develop endometriosis. Several other mechanisms for the cause of endometriosis have been proposed, including spread through the cardiovascular and lymphatic systems, spread via stem cell development, spread via surgical instruments, and more. Ultimately, we may find that different factors are present in different patients.

Whichever way the rogue cells escape the uterus, endometriosis develops when a colony of cells takes up residence in some external location and accesses a local capillary supply. From here, these cells continue to react to monthly hormonal signals to proliferate and die off, but instead of being shed with the menses, they are encased inside connective tissue cysts. Here, they accumulate and then decay in place with every menstrual cycle. Inflammatory responses make this process worse, and secondary constrictive scar tissue is a common result. This can be especially painful when growths occur on the sciatic nerve or other nerve structures in the pelvis. Scar tissue can also constrict the uterine tubes and obstruct the ovaries.

Signs and Symptoms

The signs and symptoms of endometriosis are surprisingly wide-ranging. This condition can cause any combination of these problems:

-

Anemia, fatigue

-

Chronic pelvic pain

-

Constipation, diarrhea, bloating (symptoms of irritable bowel syndrome)

-

Early signs of uterine or ovarian cancer to be missed

-

Ectopic pregnancy

-

Infertility

-

Menstrual pain

-

Mid-cycle pain and bleeding

-

Myofascial pain

-

Painful defecation

-

Painful sex

-

Painful urination

-

Pelvic and abdominal adhesions

-

Referred pain to the back, groin, and legs that can look like musculoskeletal pain

-

Uterine hyperplasia

This spectrum of symptoms is relevant to massage therapists because it can easily be mistaken for other conditions, several of which can prompt affected persons to seek our work.

The biggest caution for clients who have endometriosis is that it can cause scarring and adhesions in the abdominal cavity. This means that anything more intrusive than stroking or superficial kneading of the abdomen might cause pain and damage.

One further confusing issue with endometriosis is that the size and extent of the lesions found with laparoscopy may have nothing to do with the severity of symptoms the person experiences. It is possible for a person to have very few or small lesions and still have debilitating pain. But the opposite is also true: Some people have extensive signs of endometriosis without having any symptoms. This suggests that peripheral nerve sensitization is a bigger factor in the experience of pain than the lesions themselves.

Endometriosis can only be definitively diagnosed with a laparoscopic biopsy that shows macrophages containing hemosiderin, an iron-based by-product of red blood cell degradation. But because this is an intrusive and expensive procedure, and because the number and extent of lesions doesn’t connect well to symptoms, many doctors start with endometriosis treatment and conclude that it was an accurate diagnosis if the treatment was successful.

Treatment

Treatment options for endometriosis depend on whether the person wants to get pregnant. If they do, then treatment is geared toward limiting symptoms and progression long enough to allow conception to take place. Symptoms disappear during pregnancy, but they usually recur afterward.

Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) or other stronger analgesics may be recommended for pain relief. Hormone therapy that disrupts the secretion of estrogen may be employed to limit growths. These may be used alone or as a preparation for surgery. Surgical intervention may include the use of lasers or electrocauterization to ablate or cut out visible growths and to reduce adhesions between pelvic organs.

Frustratingly, even a uterectomy (also called hysterectomy) won’t prevent endometriosis if any remaining microscopic deposits in the pelvic cavity are stimulated with hormone replacement therapy (HRT). No permanent solution for this disorder exists until a person is postmenopausal.

What About Massage Therapy?

As we have discovered, endometriosis occurs on a wide spectrum of severity, and the pain it elicits has little to do with the extent of the endometrial growths. It is not realistic to suggest that massage therapy can “fix” endometriosis. But can our work help? Maybe.

Risks

The biggest caution for clients who have endometriosis is that it can cause scarring and adhesions in the abdominal cavity. This means that anything more intrusive than stroking or superficial kneading of the abdomen may cause pain and damage. Practitioners who are experts in visceral manipulation may have the skills to avoid causing harm, but this is best done by practitioners with advanced education.

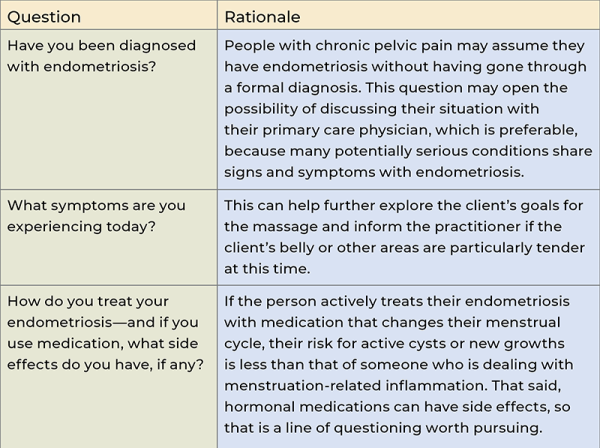

Follow-Up Questions

As we consider the other variables that inform clinical decisions for a person with endometriosis, the table below offers some important follow-up questions. These are all in addition to standard intake form questions, along with the absolutely central question for every massage session: What are your goals for massage today?

What the Research Says

The research on endometriosis, even when it doesn’t focus on massage therapy as an intervention, reveals a lot of relevant information. First, it seems clear that the neurological impact of endometriosis is as important to the symptoms as the tissue changes. This puts endometriosis into the realm of peripheral and central sensitization, where massage therapy can help “turn down the volume” on incoming nociception.¹

A randomized controlled clinical trial from Spain used manual therapy, done by a physiotherapist, to track symptoms in a group of women with endometriosis. The manual therapy involved soft-tissue manipulation, mobilization of the spine, and other techniques—most of which are within the scope of practice for massage therapists—for 30 minutes every two weeks for eight weeks. The duration of several benefits (decreased pain, improved lumbar mobility, and others) lasted for more than six months after the conclusion of treatment.²

In Your Session

Many people with endometriosis live in a state of anxiety and frustration that may exacerbate their most painful symptoms, so making time to appreciate and care for one’s body can be extremely beneficial.

Advanced education in specific abdominal and pelvic bodywork is available for practitioners who are interested in working with this population. This work may help relieve pain and other symptoms for those with endometriosis.

But even without deep work in the abdomen, it is safe to suggest that people with endometriosis can experience pain relief, emotional support, and a renewed sense of power and self-efficacy with massage therapy when it’s offered with compassion and sensitivity.

Endometriosis involves wandering cells, not wandering wombs. In some circumstances, those cells can cause a lot of problems. But our work can provide one path toward relief for clients who cope with the long-term consequences of this challenging disorder.

Notes

1. Katherine Ellis, Deborah Munro, and Jennifer Clarke, “Endometriosis Is Undervalued: A Call to Action,” Frontiers in Global Women’s Health 3 (May 9, 2022): 902371, https://doi.org/10.3389/fgwh.2022.902371.

2. Elena Muñoz-Gómez et al., “Effectiveness of a Manual Therapy Protocol in Women with Pelvic Pain Due to Endometriosis: A Randomized Clinical Trial,” Journal of Clinical Medicine 12, no. 9 (May 2023): 3310, https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm12093310.

Resources

Alexander, L. The Endo Fertility Specialist. “Could Abdominal Massage Help My Endometriosis and Fertility?” July 16, 2020. https://endofertilityspecialist.com/would-abdominal-massage-help-endometriosis-and-fertility.

ExploreGalen.com. “A Woman’s Body—Anatomy of the Uterus.” Accessed March 12, 2025. https://exploregalen.com/project/a-womans-body.

Godin, S. K. et al. “The Role of Peripheral Nerve Signaling in Endometriosis.” FASEB BioAdvances 3, no. 10 (October 2021): 802–13. https://doi.org/10.1096/fba.2021-00063.

Johns Hopkins Medicine. “Endometriosis.” Accessed March 17, 2025. https://hopkinsmedicine.org/health/conditions-and-diseases/endometriosis.

Simon, M. Wired. “Fantastically Wrong: The Theory of the Wandering Wombs That Drove Women to Madness.” May 7, 2014. https://wired.com/2014/05/fantastically-wrong-wandering-womb.

Valiani, M. et al. “The Effects of Massage Therapy on Dysmenorrhea Caused by Endometriosis.” Iranian Journal of Nursing and Midwifery Research 15, no. 4 (March 2010): 167–71. https://researchgate.net/publication/51143975_The_effects_of_massage_therapy_on_dysmenorrhea_caused_by_Endometriosis.

Zanello, M. et al. “Hormonal Replacement Therapy in Menopausal Women with History of Endometriosis: A Review of Literature.” Medicina 55, no. 8 (August 2019): 477. https://doi.org/10.3390/medicina55080477.