Treating Nerve Injuries with Massage, Part 2

Mechanisms, Techniques, and Clinical Considerations

Nerve-related pain significantly impacts quality of life and physical function, limiting mobility and diminishing someone’s ability to perform daily activities. What begins as a simple nerve compression or irritation can cascade into complex pain patterns that affect not only physical but psychological well-being. As massage therapists, we possess unique tools to address these conditions through skilled touch and client education. Massage therapy offers distinct advantages in treating nerve pain by addressing both mechanical and nonmechanical contributors. While medications primarily target chemical pain pathways, manual therapy directly affects physical compression, enhances neural mobility, and improves tissue health. Additionally, the neurophysiological effects of touch help modulate pain perception through multiple pathways in the nervous system.

In the first part of this series, we explored the physiology of nerve injuries. In this article, we’ll examine key treatment principles for nerve-related pain conditions, focusing on three primary approaches: reducing mechanical compression on neural structures, improving neural mobility through specialized techniques, and addressing systemic neural conditions with appropriate manual interventions. By understanding these principles and applying them with careful clinical reasoning, massage therapists can significantly impact outcomes for clients suffering from nerve pain conditions.

Understanding Nerve Pain: Mechanisms and Classification

In the first part of this series, we explored the physiological underpinnings of nerve pain. Before discussing treatment approaches, let’s review the three major pain categories to frame our therapeutic interventions properly.

Nociceptive pain originates from tissue damage or inflammation and represents our body’s normal protective response. This type of pain commonly appears in acute musculoskeletal injuries like sprains or strains and typically resolves as tissues heal. Massage interventions for nociceptive pain focus on promoting healing, reducing inflammation, decreasing neural irritability, and restoring normal tissue function.

Neuropathic pain results from direct nerve injury or nerve tissue dysfunction rather than damage to another tissue. Common examples include carpal tunnel syndrome, sciatica, and diabetic neuropathy. This pain often manifests as burning, shooting, or electrical sensations and may persist even after apparent tissue healing. Neuropathic pain requires specific treatment approaches that address nerve compression, neural mobility, and sensitivity.

Nociplastic pain arises from altered pain processing in the nervous system without clear structural damage. Conditions like fibromyalgia and complex regional pain syndrome (CRPS) fall into this category. This pain type involves central sensitization, where the central nervous system amplifies pain signals. Treatment approaches must address the heightened nervous system reactivity while avoiding further sensitization.

Understanding these distinct pain categories is essential because they require different treatment approaches. A technique that helps nociceptive pain might worsen nociplastic pain, and interventions effective for nerve compression might prove ineffective for systemic neuropathy. Proper assessment and classification should guide our clinical decision-making process and outcomes.

Nerve Impingement Disorders and Massage Therapy Strategies

Nerve impingement occurs when physical pressure on a nerve disrupts its normal function. This pressure can come from muscles, connective tissues, bones, or pathological structures like disc herniations. Below are common nerve compression disorders that respond well to targeted massage approaches.

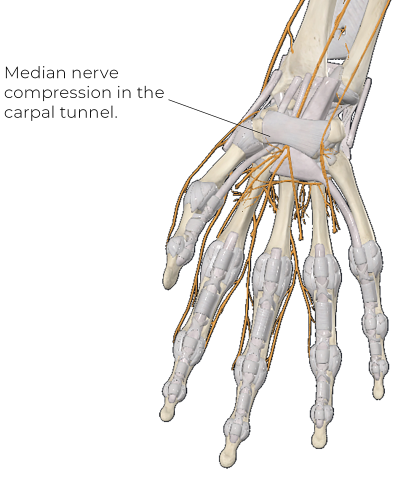

Carpal Tunnel Syndrome (CTS): This nerve impingement involves compression of the median nerve at the wrist as it passes through the carpal tunnel (Image 1). Massage therapy can significantly improve symptoms and function in CTS clients. Effective massage approaches include:

-

Soft-tissue work on the wrist flexor muscles to reduce hypertonicity that may adversely contribute to compression

-

Superficial myofascial or skin-gliding techniques that can help reduce neural irritability

-

Nerve-gliding techniques to improve median nerve mobility (Image 2)

-

Treatment of other potential compression sites to reduce their contribution to the pain (see the double crush phenomenon below)

Massage therapists should avoid direct deep pressure over the carpal tunnel, as this can increase nerve irritation. Instead, focus on surrounding structures that influence tunnel pressure and nerve mobility.

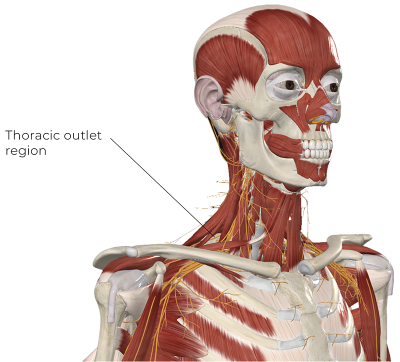

Thoracic Outlet Syndrome (TOS): This involves compression of the brachial plexus nerves and/or subclavian vessels as they pass between the scalene muscles and then between the first rib and clavicle (Image 3).

Massage therapy for TOS focuses on:

-

Reducing hypertonicity in the scalene muscles, particularly the anterior and middle scalenes

-

Reducing hypertonicity in the pectoralis minor to address its possible contribution to nerve compression in the region

-

Gentle mobilization techniques for the first rib and shoulder girdle

-

Neural mobilization for the brachial plexus and upper extremity nerves (Image 4)

These techniques help reduce mechanical compression and improve nerve mobility through the outlet. Treatment effectiveness increases when combined with appropriate postural awareness and correctly targeted exercise.

Nerve Root Compression: Also known as radiculopathy, nerve root compression commonly occurs in the cervical and lumbar spine due to disc herniation or stenosis. Direct treatment of the involved spinal segments requires careful consideration. Massage therapists should:

-

Reduce surrounding muscle guarding that may contribute to compression

-

Enhance mobility of spinal segments above and below the affected level with both general and targeted treatment strategies

-

Avoid significant pressure on spinal structures or anything that reproduces or increases the client’s existing nerve pain (Image 5)

-

Incorporate gentle neural mobilization when appropriate

Manual therapy approaches, like massage combined with therapeutic exercise, often yield better outcomes than either intervention alone.

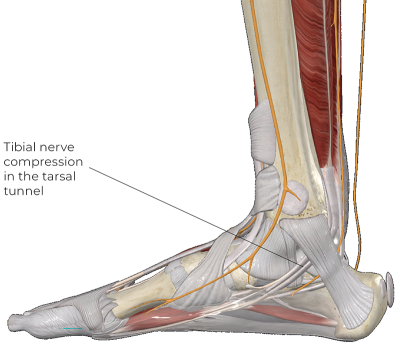

Tarsal Tunnel Syndrome: This involves compression of the tibial nerve at the ankle, often mistaken for plantar fasciitis due to similar symptoms (Image 6).

Effective massage approaches include:

-

Reducing tension in the deep posterior compartment muscles

-

Encouraging neural mobility without overstretching

-

Addressing factors of foot biomechanics, which play a major role in development

The therapist should avoid direct pressure over the nerve in the tunnel and focus instead on related soft tissues like the posterior compartment muscles that play a dominant role in condition development.

Client education represents perhaps the most critical aspect of treatment, as improper footwear remains the primary cause of this condition.

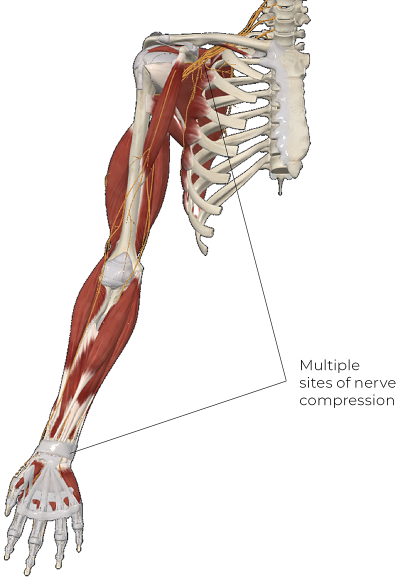

Double Crush Phenomenon and Limited Axoplasmic Transport: The double crush phenomenon occurs when a nerve is compressed at two or more locations along its path (Image 7). For example, a client might have both cervical radiculopathy and carpal tunnel syndrome affecting the median nerve. This combination creates a compounding effect, where each compression site worsens the overall nerve function.

Axoplasmic flow—the transport of essential nutrients, proteins, and signals along nerves—plays a crucial role in nerve health. When compression disrupts this flow, nerve function can deteriorate even without significant physical damage to the nerve fibers. Compromised nerve health explains why relatively minor compression can cause significant symptoms if maintained over time.

Massage therapy implications for double crush syndrome include:

-

Systematically evaluating the entire nerve path rather than focusing solely on the symptomatic area

-

Addressing multiple compression sites to relieve cumulative stress

-

Promoting fluid exchange around nerves to restore axoplasmic transport

-

Using gentle techniques to avoid further nerve irritation

Massage therapists should trace the entire nerve pathway from origin to symptomatic area, addressing any points of tension or restriction. Treating all potential compression sites yields significantly better outcomes than focusing only on the most obvious one.

Understanding Neural Tension and Restricted Nerve Mobility

Neural tension refers to increased mechanical stress on nerves due to restricted mobility. Unlike compression, which involves direct pressure, tension injuries occur when nerves cannot glide and stretch properly through surrounding tissues during movement. For example, sciatic nerve irritation often involves compression and restricted mobility when surrounding hamstring tissues limit the nerve’s free mobility. Assessment strategies for neural tension include:

-

Passive straight leg raises for sciatic nerve tension

-

Upper limb tension tests for brachial plexus and terminal nerve mobility

-

Assessment of neural mobility during functional movements

Positive neural tension tests produce symptoms along the nerve path and limit range of motion. Importantly, these tests should reproduce the client’s familiar symptoms to be considered significant.

Understanding the neurophysiology of central sensitization helps therapists avoid approaches that might reinforce pain cycles.

With neural tension disorders, the primary goal is to enhance surrounding tissue pliability, so there is the best opportunity for increasing neural mobility. Massage and neural mobilization techniques for neural tension include:

-

Reducing soft-tissue restrictions around nerve pathways

-

Addressing muscular tension that restricts nerve movement

-

Nerve-gliding techniques that gently mobilize nerves through their full range

Neural gliding, or “flossing,” techniques involve specific movement sequences that alternately tension and slack different portions of a nerve. For example, a median nerve glide might combine wrist extension (which tensions the nerve distally) with elbow flexion (which slackens it proximally), followed by the reverse movement. These techniques improve nerve mobility without excessive stretching at any single point. Yet, they also require careful application, as excessive force can worsen nerve irritation.

The Role of Inflammation and Chemical Irritants in Nerve Pain

Beyond mechanical factors, chemical irritants significantly contribute to nerve pain. When tissue inflammation occurs near a nerve, inflammatory mediators can directly sensitize nerve endings, leading to neuropathic pain even without physical compression. Several key inflammatory mediators influence nerve pain:

-

Phospholipase A2 (or PLA2) is an enzyme linked to inflammation-related nerve damage, particularly in disc herniations affecting nerve roots.

-

Cytokines and prostaglandins promote pain hypersensitivity and nerve irritation.

-

Substance P and other neuropeptides enhance pain signaling.

For example, in sciatic nerve irritation from disc herniation, inflammatory chemicals from the damaged disc often cause more pain than the physical compression itself. This systemic reaction explains why some people with minimal disc bulges experience severe pain while others with significant herniations remain asymptomatic. Massage considerations for chemically mediated nerve pain include:

-

Gentle techniques promoting circulation and lymphatic drainage to reduce inflammatory mediators

-

Working in pain-free regions initially to avoid exacerbating inflammation

-

Progressive introduction of more direct techniques as inflammation subsides

-

Avoiding aggressive techniques that could trigger inflammatory responses

While we need more research, there is some indication that manual therapy influences pain partly through modulating these inflammatory pathways. Massage cannot directly remove chemical irritants, but it can create conditions that promote clearance and inhibit production.

Addressing Systemic Neural Conditions

Some neural pain conditions stem from systemic issues rather than localized compression or tension. These conditions require specialized approaches that consider the heightened sensitivity of the nervous system.

Fibromyalgia: This involves widespread pain with heightened nervous system sensitivity. Massage approaches for fibromyalgia often include:

-

Gentle, rhythmic techniques to reduce nervous system hyperactivity

-

Gradual progression of pressure and depth based on tolerance

-

Consistent treatment schedules to avoid symptom flares

-

Focusing on improving sleep and reducing stress, which directly affect pain levels

Complex Regional Pain Syndrome: This neural condition presents as severe pain following injury, with autonomic nervous system involvement causing temperature, color, and sweat changes in the affected limb. Massage approaches include:

-

Very gentle initial contact, often beginning with nonpainful body regions

-

Slow, graded exposure to manual therapy

-

Desensitization techniques to progressively introduce different sensory stimuli

-

Collaboration with other health-care providers in a multidisciplinary approach

The massage therapist must respect pain boundaries while gently challenging them, using the concept of graded exposure to help normalize sensation in affected areas.

Peripheral Neuropathy: Including diabetic neuropathy, peripheral neuropathy involves nerve damage leading to numbness, tingling, and burning pain, typically in the extremities. Effective massage approaches include:

-

Light, circulation-enhancing techniques to improve blood flow to affected nerves

-

Lymphatic drainage to reduce edema that may contribute to nerve compression

-

Gentle mobilization of tissues surrounding major peripheral nerves

-

Attention to foot care and positioning to prevent further damage

Massage cannot reverse nerve damage but can improve symptoms and potentially slow progression by enhancing circulation and reducing factors that worsen neuropathy.

Central Sensitization and Chronic Pain Syndromes: These syndromes occur when the nervous system becomes hypersensitive to normal stimuli. For these conditions, massage therapists should employ:

-

Soothing, nonaggressive touch that doesn’t trigger protective responses

-

Mindfulness-based bodywork to help clients process sensations differently

-

Techniques that activate descending pain inhibition pathways (usually soothing, gentle gliding techniques)

Understanding the neurophysiology of central sensitization helps therapists avoid approaches that might reinforce pain cycles while choosing interventions that promote nervous system regulation.

Key Takeaways for Massage Therapists

Understanding the nature of nerve pain is critical to safe and effective treatment. As massage therapists, we must recognize that nerve pain differs fundamentally from nociceptive pain in both mechanism and treatment approaches.

Mechanical approaches focus on alleviating nerve compression, enhancing mobility, and releasing tension in surrounding tissues. These interventions directly address physical factors that irritate nerves and restrict their function. However, we must apply these techniques precisely, understanding which structures we’re targeting and why.

Chemical influences like inflammation play a significant role in neuropathic pain and require gentler approaches that promote healing without exacerbating irritation. Sometimes, the best strategy initially involves working away from the painful site and only gradually introducing more direct treatment as tolerance improves.

Systemic nervous system disorders require careful, individualized approaches that consider the unique presentation of each client. The heightened sensitivity in these conditions means that techniques effective for typical pain may prove counterproductive or even harmful.

Massage therapy provides a valuable tool for addressing nerve pain, but practitioners must adapt techniques based on pain type, severity, and individual response. Through careful assessment, thoughtful treatment planning, and ongoing reevaluation, massage therapists can significantly improve outcomes for clients suffering from nerve-related pain conditions. By integrating this knowledge of nerve pain mechanisms with skilled hands-on techniques, massage therapists occupy a unique position in helping clients overcome these challenging conditions and return to fuller, more comfortable function.