Rotator cuff disorders are prevalent musculoskeletal injuries that affect millions worldwide each year. This complex of muscles and tendons tasked with stabilizing the shoulder joint is often subjected to overuse, strain, and injury. The subsequent pain, weakness, and mobility loss can profoundly impact daily life and activities.

Understanding these disorders is crucial for helping clients alleviate painful and debilitating shoulder problems, and the prevalence of rotator cuff injuries means you will almost certainly encounter them in your practice. With a thorough comprehension of the rotator cuff’s anatomy, physiology, and pathology, we can provide targeted interventions that alleviate symptoms and aid in optimum function.

This is a two-part series, and in this first article we dive deep into rotator cuff disorders, their causes, and their symptoms. We’ll explore key strategies for identifying the tissues involved in your client’s shoulder pain complaint and delve into the factors influencing effective treatment and beneficial options for treating rotator cuff disorders.

Anatomy and Kinesiology Review

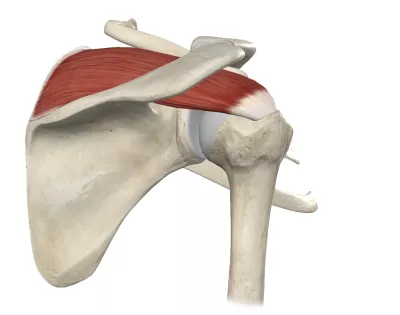

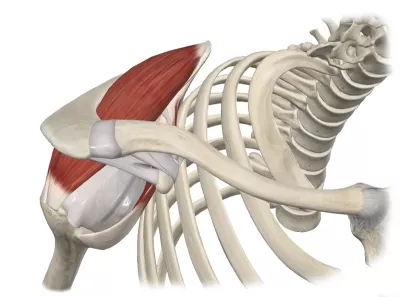

Let’s begin with a comprehensive look at the rotator cuff’s structures. The rotator cuff is a group of four muscles surrounding the glenohumeral joint, consisting of the supraspinatus, infraspinatus, teres minor, and subscapularis. The supraspinatus spans from the supraspinous fossa of the scapula, passing underneath the acromion and attaching to the superior facet of the greater tubercle on the humerus (Image 1).

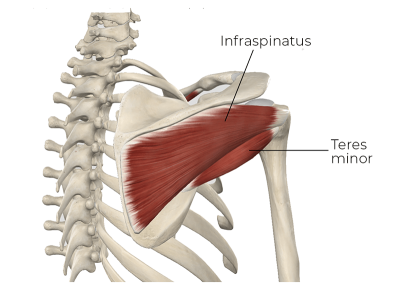

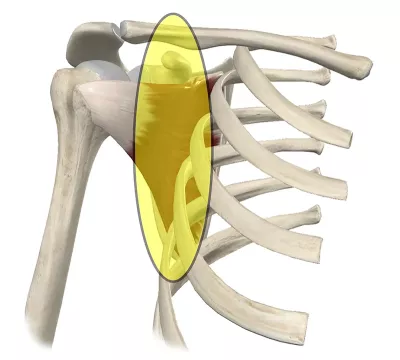

The infraspinatus and teres minor both originate from the posterior scapula, attaching to the middle and inferior facets of the greater tubercle, respectively. Notably, the infraspinatus is the larger of the two (Image 2).

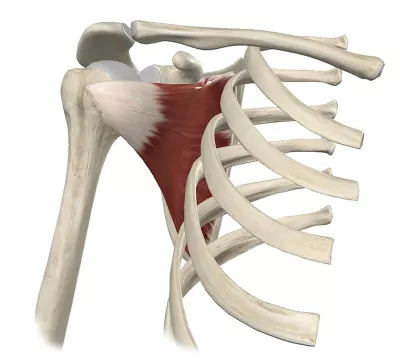

The subscapularis spans from the subscapular fossa to the lesser tubercle of the humerus (Image 3).

The supraspinatus initiates abduction, lifting the arm away from the body. The infraspinatus and teres minor provide external rotation, enabling movements such as reaching behind your head and decelerating the arm motion in throwing. The subscapularis, being the internal rotator, assists in actions like scratching the lower part of your back or reaching down to tie your shoes. You likely memorized each of the rotator cuff’s muscles with their main actions mentioned above, but a proper understanding of their importance must include a focus on glenohumeral stability.

The glenohumeral joint has the greatest range of motion of any joint in the body. However, this range of motion sacrifices stability for movement, lacking many larger, restraining ligaments characteristic of other major joints. Consequently, the rotator cuff muscles also play a critical role in joint stability.

One of the ways the rotator cuff muscles enhance stability in the joint is by fusing with the ligaments of the glenohumeral joint capsule. The rotator cuff muscles at the distal end blend into the glenohumeral joint capsule before attaching to the humerus. Nowhere else in the body is there such a close functional relationship between the muscles crossing the joint and the binding capsule of the joint.

Aiding joint stability by holding the humeral head close into the glenoid fossa requires highly complex muscular control because the shoulder’s range of motion is so great. Different muscle recruitment patterns are required at all these different joint positions. The rotator cuff muscles can carry out these crucial coordination patterns because of the exceptionally rich collection of sensory receptors in the glenohumeral region. The richly innervated connective tissues in the region feed critical sensory information to the nervous system to help regulate proper muscular control and function. The necessity for precise sensory control is one of the reasons exercise plays such an essential role in rehabilitating the rotator cuff.

Given the crucial nature of these functions, rotator cuff disorders can dramatically impact daily life, limiting functional capacity and causing significant discomfort. Understanding this dynamic is the first step toward offering effective care to those we serve. So, let’s look at some of the most common rotator cuff disorders.

Rotator Cuff Disorders

Rotator Cuff Tears

A rotator cuff tear is a muscle strain affecting one of the rotator cuff muscles. A muscle strain is usually graded as mild, moderate, or severe. Mild rotator cuff tears may have minimal discomfort and heal quickly on their own. Severe tears will often need surgical repair and a highly focused regimen of exercise rehabilitation after the surgery.

Of the four rotator cuff muscles, the supraspinatus is strained most often. This is mainly because it is vulnerable to repeated compression damage and fraying under the acromion process of the scapula. It is also under the highest demand in shoulder actions, so supraspinatus tears often result from cumulative loading over time.

Supraspinatus tears are either partial or full-thickness tears. In a partial-thickness tear, only a portion of the tendon is damaged, leaving some tissue intact. In contrast, full-thickness tears involve complete separation of the tendon from the humerus. Symptoms include pain, weakness, and limited shoulder mobility, especially during overhead activities.

The causes are usually multifactorial, including age-related degeneration, overuse (especially repetitive overhead movements), and acute injury (such as falls or sudden lifting). Over time, these factors can lead to microtears, inflammation, and eventual tearing of the tendon.

Infraspinatus and teres minor tears are the next most frequent. Tears in these muscles usually occur close to the musculotendinous junction, where the two muscles blend together. It is hard to determine which of these muscles is torn, so the condition is referred to as a posterior rotator cuff tear. These tears often result from high force loads when decelerating the arm, like at the end of a throwing motion.

Subscapularis tears occur, but are the least common of the four rotator cuff tears. This is mainly because other muscles perform the same actions as the subscapularis and help absorb the excessive loads that might cause a strain.

Rotator Cuff Tendinosis

Formerly, this condition was called tendinitis (indicating inflammation in the tendon), but recent research suggests that chronic-overuse tendon disorders can have minimal inflammatory activity. Instead, the primary pathology involves a breakdown in the collagen matrix of the tendon.

Tendinosis results from chronic overuse—particularly repetitive, overhead arm movements—leading to wear and tear on the tendon fibers. Aging also plays a role, as blood supply to tendons decreases, impairing their ability to heal and regenerate.

Symptoms of tendinosis are subtle, often presenting as a dull ache in the shoulder that worsens with use. Over time (if left untreated), degeneration can lead to a complete tear of the tendon.

Subacromial Impingement Syndrome

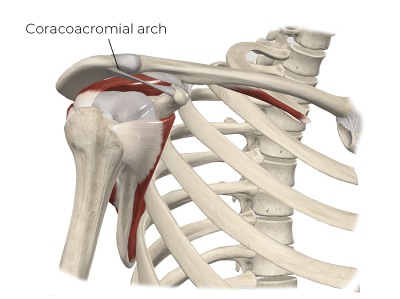

Impingement syndrome occurs when the rotator cuff muscle and tendon fibers become compressed under the coracoacromial arch. The coracoacromial arch is created by the acromion process, the coracoid process, and the coracoacromial ligament that spans between them (Image 4). The teres minor and infraspinatus don’t course under the coracoacromial arch because they are on the back side of the glenohumeral joint. Consequently, they are not involved in subacromial impingement.

In subacromial impingement, the supraspinatus or subscapularis muscle-tendon units may get repeatedly squeezed or pinched during shoulder abduction or flexion. Certain anatomical variations can make the subacromial space tighter and the muscles more susceptible to compression. Repetitive overhead motions or various degenerative changes also lead to subacromial impingement.

Evaluation Considerations

A detailed client history and initial assessment provide valuable insights into potential rotator cuff disorders. A history of repetitive overhead activities, trauma, or significant age-related degeneration might suggest underlying tendinosis or impingement syndrome. A client may report sudden acute pain and weakness in more severe cases, often indicating a possible tear.

Pain that worsens at night or when lying on the affected shoulder is common with rotator cuff disorders. However, it can also indicate subacromial bursitis, so don’t immediately assume that night shoulder pain is a rotator cuff problem. While the specific symptoms can vary, common themes with rotator cuff disorders include shoulder pain, weakness, and limited mobility, particularly during overhead activities.

A comprehensive physical examination remains one of the most effective ways to identify when the rotator cuff muscles are likely involved. Unfortunately, many clients have never had a thorough physical examination with specific movement testing. Because of the time we spend with our clients, massage therapists have the opportunity to be very thorough with our clients’ assessments.

Specific musculotendinous tissue injury, like that involved with rotator cuff disorders, generally shows a characteristic pattern in the physical exam. Pain will likely be reproduced with three key factors: palpation, stretching, and manual resistance. Identifying which specific motions reproduce your client’s pain is valuable in guiding the treatment. The teres minor and infraspinatus are relatively superficial and reasonably easy to palpate. The proximal supraspinatus belly can be palpated where the muscle sits in the supraspinous fossa. However, the musculotendinous junction is usually inaccessible to palpation as it courses under the acromion process (Image 5).

Unfortunately, most supraspinatus disorders occur at or near this musculotendinous junction, making palpation difficult. Subscapularis disorders near the distal musculotendinous junction can be palpated as the tendon courses around the anterior aspect of the humerus. If the subscapularis injury is farther back in the belly of the muscle, it will be inaccessible to palpation (Image 6).

Pain in a damaged rotator cuff muscle is easier to identify with stretching as long as you remember the key actions of those muscles. Stretching the supraspinatus in pure abduction is challenging because the arm hits the body. However, you can pull the arm across the front of the body to stretch it more effectively. The infraspinatus and teres minor will be effectively stretched by moving the shoulder into medial (internal) rotation. Pathology in these muscles or their associated tendons will produce pain in the posterior aspect of the shoulder. The pain may occur more on the lateral shoulder near the end range of medial rotation because the attachment site is rolling around from the posterior to the lateral side. Subscapularis dysfunction will produce pain with lateral (external) shoulder rotation and is usually felt more toward the front side of the shoulder.

When pathology involves a muscle-tendon unit, pain is commonly reproduced with a manual resistive test (MRT). The MRT engages the tissues in a contraction with moderate force. Supraspinatus involvement will be most effectively tested with resisted abduction. This test is performed with the client’s arm at about 45 degreesof abduction. The practitioner will place one or both hands just above the client’s elbow and instruct the client to hold the position while the practitioner pushes down on the client’s arm with just a moderate amount of force. Supraspinatus pathology usually produces some degree of lateral shoulder pain with this test.

Testing the posterior rotator cuff muscles (infraspinatus and teres minor) and anterior cuff subscapularis can use the same starting position. The client keeps their upper arm at their side, and the elbow is flexed so the forearm points straight forward. The practitioner will place their hand on the client’s wrist. The posterior rotator cuff muscles are evaluated with resisted lateral rotation. For this movement, the practitioner places their hand on the dorsal surface of the client’s wrist and tries to medially rotate the client’s arm with moderate force. The client will resist that action. Pain on the posterior aspect of the shoulder with this movement is frequently indicative of tissue involvement with one or both posterior rotator cuff tendons.

The subscapularis is tested in the same starting position as the posterior rotator cuff tendons, except the practitioner places their hand on the wrist’s anterior (volar) aspect. The client will be instructed to hold the position as the therapist attempts to laterally rotate the shoulder by pushing outward on the distal forearm with moderate force. Subscapularis pathology generally produces pain in the anterior shoulder region with this test.

While massage therapists do not perform diagnostic imaging, understanding its role and limitations in identifying rotator cuff pathologies can enhance client education and interprofessional communication. X-rays can reveal bony changes, such as spurs or degeneration, which can contribute to impingement. However, X-rays don’t provide a clear view of soft tissues, so their use in diagnosing rotator cuff disorders is limited.

Ultrasound imaging provides real-time dynamic images of soft tissues, including tendons and bursae, and can reveal thickening, tears, or inflammation. Additionally, its noninvasive and cost-effective nature makes it an accessible choice for many. MRI provides the most detailed images of soft tissues, including the rotator cuff tendons, and is often used to identify more severe tissue damage to the rotator cuff. However, there are many cases where soft-tissue dysfunction is significant enough to cause pain but does not appear well in these high-tech diagnostic studies. That is why a detailed physical exam—which massage therapists trained in assessment can undoubtedly perform—is so valuable.

Conclusion

Shoulder pain is a common reason for clients to seek our help. The shoulder is a complex joint, and because soft tissues are so crucial in the shoulder’s function, they are also often implicated in pain problems, making it essential to understand the structure, mechanics, and evaluation strategies for the tissues in this region. In my next article, we’ll look at some crucial factors governing the effective treatment of these disorders and highly effective treatment options.