There are many contacts to use when performing massage therapy. These range from thumb pad and finger pads as the smaller contacts, to elbow and forearm as the usual larger contacts (Images 1A-1D). The advantage of smaller contacts is they are the most sensitive and best at assessing tissue texture and tone; they are also better at reaching deeper into tissue. The disadvantage of using smaller contacts is the joints are smaller and therefore more vulnerable to injury with repeated use. They also cover less area of the client’s body and tend to feel a bit pokey to the client. The advantage of larger contacts is the joints are larger and therefore stronger and less vulnerable to injury; also, being larger, they cover more surface area of the client’s body. However, they are not as sensitive as the smaller contacts. Also, the olecranon process of the elbow and the medial shaft of the ulna are hard and bony and can be uncomfortable for the client, especially when used on bony areas of the client’s body (where bone is close or immediately deep to the skin). So, I would like us to consider the palm as a contact when doing massage therapy.

Variations of Using the Palm

Many therapists already use the palm, but I believe there are variations with its use that are not always fully appreciated. And these variations render the palm, in my opinion, as perhaps the best contact in massage, and the contact that I use the most when working on patients. Why is the palm such a good contact? It is broad and strong, somewhat like the elbow or forearm, but much softer and comfortable for the client because of the cushioning of the myofascial tissue of the thenar and hypothenar eminences. And when we angle the palm by supinating or pronating the forearm, we can diminish the size of the palm contact, making it much more specific without being pokey the way thumb and finger pads can be.

Full-Flat Palm

When the palm is used in massage, most therapists use the full-flat palm (Image 2). The full-flat palm is a wonderful contact because, as stated, it is broad, strong, and stable, and covers a large amount of surface area of the client’s body; but it is not hard or pokey. And it can be easily braced/supported. Bracing a contact is extremely valuable toward having good body mechanics that allow for career longevity. By bracing a contact, we support the structure of the joint, which preserves the fascial tissue of the ligamentous/joint capsule complex, preventing overstretching and injury of the joint. We also decrease compression forces through the contact joint because bracing allows for the physical stress of the stroke to be spread across both upper extremities. In other words, the brace-side upper extremity does not just protect the contact, it also contributes to the force of the stroke.

Bracing/Supporting the Palm

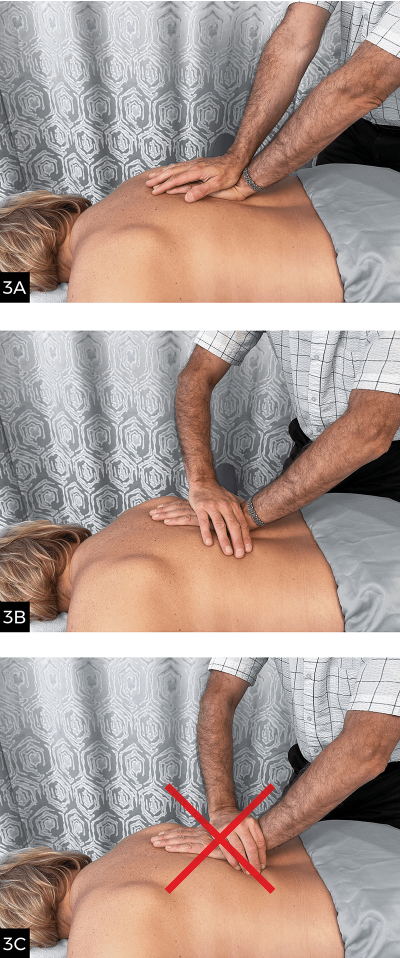

There are two easy ways to brace a full-flat palm. Image 3A shows what is likely the most common brace used: that is, to use the palm of the other hand. This brace works very well when the palm is fully flat. However, it is not as versatile a brace for when we want to orient away from the full-flat palm and angle it to use more of the hypothenar eminence or the thenar eminence.

For full versatility of the palm, I recommend using the thumb-web brace shown in Image 3B. For the thumb-web brace to be used effectively, the actual web of the thumb needs to be placed directly over the carpal region at the base of the palm where the pressure of the contact hand is contacting the client. Often, therapists will err and instead brace the contact hand/forearm as seen in Image 3C, with the ulnar side of the support hand on the dorsum of the contact hand, and the thumb web up high on the distal forearm. This leaves no support to the actual contact region at the base of the palm that meets the client’s body.

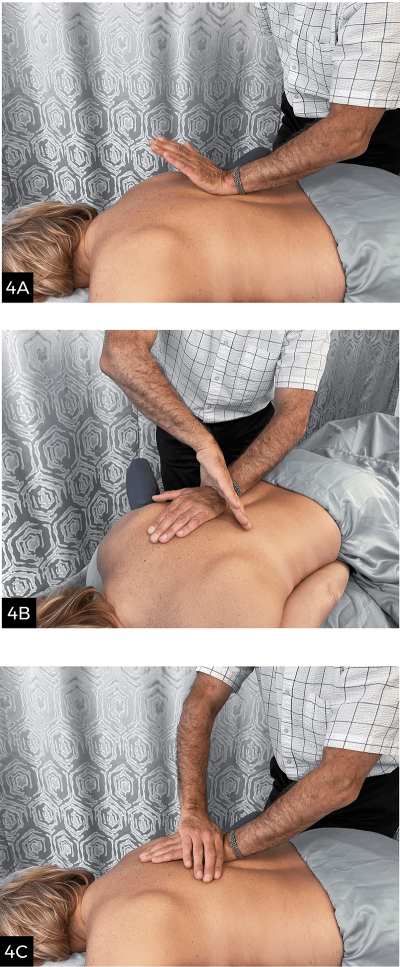

One way to learn how to effectively employ the thumb-web brace for the full-flat palm is to first place the palm as a contact on the client but exaggerate the ability to see the contact by extending the hand at the wrist joint (Image 4A). Then place the thumb-web support directly over the base-of-the-palm contact but exaggerate the position of the support upper extremity by pronating the forearm (Image 4B) so that we can better visualize where the thumb web supports the contact hand. This positioning shown in Images 4A and 4B is not comfortable or relaxed for the therapist; it is just done to help us better understand the positioning of our hands. So, now let both hands relax as seen in Image 4C. Comparing this thumb-web brace with the opposite-side palm brace (Image 3A), you can see that the disadvantage of the thumb-web brace is that the elbow of the brace-side upper extremity is out a bit, which means the brace-side glenohumeral joint is slightly in medial/internal rotation, which is not the ideal posture for the shoulder joint. However, where the thumb-web brace really shines is how it allows for the versatility of the orientation of the palm as a contact.

Angling the Palm Contact

One of the major advantages of the full-flat palm is that it is broad (Image 5A). However, this can also be a disadvantage because the contact may be too broad to allow work in certain areas and/or contours of the client’s body—for example, when performing a long deep stroke up the client’s back along the paraspinal musculature. In the low back, there is plenty of room for the palm to be fully flat. But as we reach the interscapular region (between the scapulae) in the thoracic spine, there is often not enough room between the medial border of the scapula and the spine. Instead of switching to another contact, we can simply supinate the forearm to orient the palm so that we are pressing more on the hypothenar side of the palm instead of the full-flat palm (Image 5B). This narrows the contact, allowing seamless passage of this stroke through this area to continue to the top of the client’s trunk. We still have a strong contact, but one that fits between the scapula and spine. We also can even focus the force of our stroke through the pisiform of the hypothenar eminence (Image 5C).

There is an art to learning to use the pisiform, and it can take time to master, but it is well worth it. The pisiform is a small bone, so it is very specific in its contact, but it is a round bone, so it is not pokey for the client. Further, because it is surrounded by the myofascial tissue of the hypothenar eminence, it is padded and even more comfortable for the client and the therapist. We can even transition our contact to be fully on the ulnar side of our hand (Image 5D). The ulnar-side contact is often referred to in manual and movement therapy as the knife-edge contact.

An alternative orientation of the palm is to instead pronate the forearm to orient the palm toward the thenar eminence (Image 6A). This also allows for a strong but smaller contact than the full-flat palm. And to focus the force of the stroke, we can orient the palm such that we place our force through the tubercles of the trapezium and scaphoid (Image 6B). Whether it is best to orient toward the thenar eminence or the hypothenar eminence depends on the contour of the client’s body that we are trying to meet. Most often, the hypothenar side is most advantageous. But the flexibility of being able to seamlessly switch from full-flat palm toward thenar or hypothenar eminence and back allows for a much greater efficiency of our work.

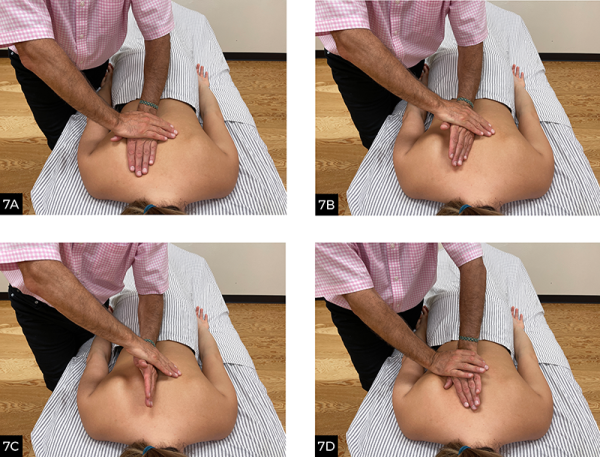

Thumb-Web Brace for Oriented Palm

Orienting the palm for a focused hypothenar, thenar, or ulnar-side contact is where the use of the thumb-web brace shines. Although the opposite-side palm brace (Image 3A) works very well when employing the full-flat palm as the contact, it does not allow for comfortable changes in the orientation of the palm toward the hypothenar eminence, thenar eminence, or the ulnar side of the hand, whereas the thumb-web brace does allow for transitioning from full-flat palm to these other more focused contacts of the palm (Images 7A–7D). The ability to seamlessly move between these strong, broad, and comfortable contacts, with bracing for both increased strength and efficient body mechanics, can bring orthopedic therapeutic massage to a new level, especially when working with deeper pressure.

Angle of Our Forearms

When working with the thumb-web brace for a palm contact (whether it is the full-flat palm or a hypothenar-oriented or thenar-oriented palm), the force for the pressure can be generated from either-side upper extremity, or both upper extremities. In other words, the brace-side hand can contribute to the force of the stroke. The degree of contribution can vary from adding perhaps 10–20 percent of the force, to being 50 percent of the force, to even being the majority, or even all, of the force of the stroke. This is important because it allows for us to change the angle of our forearms, which in turn changes the angle of our wrist joints. For example, if we have the contact-side hand generate all the force, then if we want to meet the contour of the client’s body perpendicularly (which allows for maximal pressure with minimal effort), then the angle of the forearms would need to be vertical, which would then require the posture of our wrist joint to be in full or near-full extension (Image 8A). This could be injurious to therapists’ wrists.

The ability to seamlessly move between these strong, broad, and comfortable contacts can bring orthopedic massage to another level.

If instead, we share the force of the stroke 50/50 between the contact and brace hands, then we can change the angle of our forearms to be less vertical, allowing our wrist joints to be in less extension (Image 8B). But the resultant force is still vertically downward and perpendicular to the contour of the client’s body. We maximize the efficiency of our force, and with a healthier posture to our wrist joints. Of course, we do not want to angle our forearms too horizontally, or we lose the ability to transfer force from our core into the client (Image 8C).

Quantity of Strength, Quality of Feel

There are many choices for contact when performing manual therapy. Each contact has advantages and disadvantages. When deciding between smaller and larger contacts, I hope you consider the palm as perhaps the ideal middle-sized contact because of the advantages that it shares with both smaller and larger contacts. And beyond the consideration of the size of the palm contact, there is also the quality of the feel of the palm as a contact. Its strength and stability are matched by its comfort because of the surrounding myofascial tissue. And when you learn how to change the orientation of the palm to focus toward the hypothenar eminence and its pisiform, or the thenar eminence with its trapezium/scaphoid tubercles, the specificity and efficiency of our work increases multifold. So, consider the palm for its quantity of strength and its quality of feel.

A Deeper Dive—Other Contacts

Knuckles and Fists—There are a few other contacts that can be used with clients. Two of these are knuckles and fists. Albeit very stable contacts, knuckles and fists are hard and bony and, if used, they should only be used in areas of the client’s body that are fleshy. Using a bony contact over a bony area of the client’s body can be uncomfortable for the client. Speaking as a regular client of massage therapy, one of my pet peeves is when a therapist uses a bony contact over a bony area. Ouch!

Feet—Feet are another contact used, especially in Asian massage practice. The feet are strong contacts, especially given that body weight is usually used when working with the feet. And the feet are broad and cushioned, and therefore very comfortable contacts for the client.

Tools—When massage therapy tools are considered, although they may be employed to decrease stress to the practitioner’s thumb and finger joints, the trade-off is that they, like bony contacts, tend to be hard, so the choice of where to use them should be strategically integrated into our work. And because we are not directly contacting the client’s body when we use tools, they decrease practitioners’ ability to sense the response of the client’s tissues to our work.