I hurt my knee skiing yesterday. Shoving my ski instead of carving it through a steep turn, I lurched and felt a searing pop on the inside of my knee. Weight-bearing felt OK, but any tibial abduction or external rotation made me nauseous with pain. Today, almost any knee movement hurts. Suddenly, instead of being the alleviator, I’m the afflicted. What a switch! I am reeling a bit from the change in perspective.

Rather than heading out first thing for my daily walk or run, I’m in bed, pondering my immobility. I have all the usual early-morning restlessness that gets me out into the snowy predawn fields around my house. But now, with most movement painful, I’m left with just the restlessness.

As a daily mover, I’ve wondered what I would do if I couldn’t run or walk. I’ve imagined I’d get more creative with upper-body activity. Easy to say . . . at this moment, waking up on the first day after getting injured, I’m seeing all the barriers and limitations more than I’m seeing the possibilities.

In my 20s, I spent a couple of months in a brace after injuring the same knee in a motorcycle wreck. The forced immobilization made me sit with things I wasn’t taking time for in a way that was ultimately really great. I wonder what’s ahead this time?

Day 3

With my routines disrupted, I lie in bed updating my knowledge about medial collateral ligament (MCL) injuries. It is a well-connected and multilayered structure, with its named portions including the deep MCL, the superficial MCL, and the posterior oblique ligament (POL). The POL is the main structure I probably injured, based on what I feel, the twisting mechanism of injury, and my lack of a posterior cruciate ligament (ruptured playing wallyball 15 years ago) that normally would help resist the external tibial rotation that produced that loud pop on the ski slope.

Commonly injured, the MCL and POL either: (a) usually repair themselves, even when torn (say the rehab-physio sources, which I like hearing), or (b) need early surgical intervention when fully torn (say the orthopedic surgeons, which I don’t like hearing at all).

So, to determine the extent of my injury, I start the many-phased process of getting an orthopedic evaluation, which means entering into the complex and agonizingly slow medical-care system. Filled with mostly good intentions and good people, the medical-care system is necessarily very complicated and very careful. It’s also frustratingly unadaptable and bureaucratic. So, I try not to think about Franz Kafka as I spend a large portion of my day in waiting rooms, meditating instead on the gratitude I feel for the privilege of having such a sophisticated and well-funded system available to me.

Day 4

I continue to be a fascinated observer of my MCL injury’s changes. Four days in, the searing pain has diminished quite a bit as the inflammatory progression starts to move beyond the acute stage. In theory, the nociception-generating cytokines, kinins, and other irritating proteins are much less concentrated in my knee’s inflammatory soup, and the phagocytosis and enzymatic destruction of the damaged tissues is starting to diminish. So, my free nerve endings are less irritated and generating less nociceptive signal; less signal means less pain experience, less pain means I move more, which helps further flush those irritating proteins out of the sensitized areas. My brain is happy.

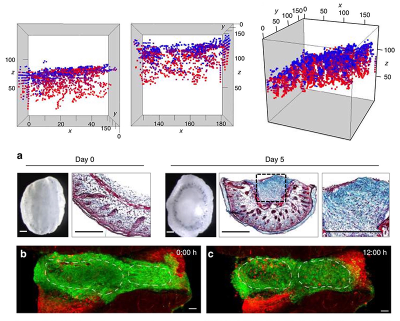

Speaking of happy, my friendly fibroblasts started working within minutes of the injury, and as the riot of acute inflammatory processes continues to calm down, those fibroblasts will move into greater prominence. They’re helping now with further inflammatory control, as well as starting new tissue proliferation. More of that to come!

Day 10

My knee is well into the tissue-repair and adaptation phase. I’ve been an active observer of my body’s many recovery processes, gently nudging them along with a sumptuous potluck mix of interventions, including:

- Physiotherapy with Adele by Zoom from Israel

- Zoga movement with Wojtek Cackowski by recording from Poland (and Jessica Garcia, Zooming in from Puerto Rico)

- Gentle hands-on, in-person manual therapy from myself and my wife, Loretta

- Weights, bands, machines, and gravity exercises (really not my thing but, hey, I’m working on that)

- Bracing, saunas, cupping, taping, collagen, rest, etc.

- But, no ice and no nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, no way—at least not in the beginning phase. Swelling is not my adversary; knee pain is minimal (except when I mistreat it, which pain relievers do not prevent); and inflammation’s progression is how healing happens. Why would I want to inhibit that?

- And in the last couple days, I am finally venturing out for some walks, gradually longer, fully equipped with a super-brace, poles, and ice-crampons for stability on the crusty ice and snow around my house.

Then, I rest and “feel”/imagine the gossamer but fibrous mats of new fibroblast-generated tissues being woven into my injured areas, and gradually migrating up and out to form lattices for continued tissue strengthening and repair.

Day 20

Good news, and potentially bad news, on the path to ski-accident recovery. The good news: My MCL injury is making an amazing recovery. The things that were so excruciatingly painful less than three weeks ago now feel nearly normal, both to touch and to use. The first couple of days, just getting off the bed was an epic challenge that would leave me shaken, perspiring, and ashen from the pain.

Fast-forward to these last few days, when a four-mile hike with my son, over uneven ground, and in the dark, evoked almost no soreness and left me yearning for more.

The potentially bad news: My orthopedic-assessment appointment finally came, and the physician’s assistant (PA) who examined me was sure I have a ruptured anterior cruciate ligament (ACL). And his news-delivery skills sucked, in my opinion: “Whoa, your ACL is totally torn. Wow, I’m so sorry man, that’s really a bummer. You’re almost fershur going to want ACL surgery, and then a long recovery, six, no, probably nine months, before you’re back.” Maybe he even said, “Sorry, dude.”

Granted, I’m probably a tough customer, and to be fair to the poor guy, my annoyance with him as the messenger was mixed with my clear dislike of the message. I didn’t want to think my ACL was torn, even though I knew there was a decent possibility that it was injured along with my MCL (and maybe my medial meniscus too). As the outer tissue layers have healed and become less painful, deeper sensations of guarding, sensitivity, and pain have come to the fore. A drawer test was negative at first (a good sign), though maybe just because there was so much guarding then. Now (in my opinion at least), the test is more ambiguous, my PA’s certainty notwithstanding.

But I’m biased. After all, it’s my knee! Strange, though, how my bias bounces around. I’m still watching myself with amazement as my own certainty pendulum swings back and forth between extremes, starkly influenced by the latest diagnosis. Sometimes (like after the PA consult), I’m absolutely resigned to the “fact” that my ACL is blown out; other moments (like after a different practitioner’s assessment of “not much difference” between the two knees), I think maybe it’s probably just a grade 1 or 2 strain.

This fluidity of my inner reality isn’t that different from outer-world knee-assessment results: In one systematic review, inter-rater reliability of the best manual ACL test (Lachman’s) “ranged from slight to almost perfect.”3 That means in some cases, there was almost no match between different practitioners’ conclusions for the same patient; in other patients, practitioners were in almost perfect agreement with each other. (Speaking of guarding, Lachman’s test is considered much more reliable when performed on anesthetized subjects, which I haven’t yet tried on myself.)

I’m scheduled for an MRI in about a month. I don’t expect the MRI to necessarily answer all my questions, no matter what it shows. In the meantime, I’m celebrating the ever-increasing confidence and comfort I feel in my knee. And meanwhile, I’ve been using my super-brace less and less, with today (Day 20) being my first 100 percent brace-free day. Still feeling great. We’ll see what the coming month brings.

Notes

1. D. Guenther et al., “Treatment of Combined Injuries to the ACL and the MCL Complex: A Consensus Statement of the Ligament Injury Committee of the German Knee Society (DKG),” Orthopaedic Journal of Sports Medicine 9, no. 11 (2021), https://doi.org/10.1177/23259671211050929.

2. D. Jiang et al., “Injury Triggers Fascia Fibroblast Collective Cell Migration to Drive Scar Formation Through N-Cadherin,” Nature Communications 11, no. 5653 (2020), https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-020-19425-1.

3. Toni Lange et al., “The Reliability of Physical Examination Tests for the Diagnosis of Anterior Cruciate Ligament Rupture—A Systematic Review,” Manual Therapy 20, no. 3 (2015): 402–11, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.math.2014.11.003.