Clients often walk into a massage therapy session describing sciatica, a catch-all term that typically means they’re experiencing pain somewhere along the back of the leg. For the massage therapist, this type of client pain should elicit both an opportunity to help the client and caution. On the one hand, sciatic pain is common and, in many cases, can be helped with skilled massage treatment. On the other hand, the symptoms can stem from a range of underlying conditions—some within the massage therapist’s scope of practice, and others that require prompt referral to a physician or specialist.

Understanding sciatic pain starts with this important truth: Sciatica is a symptom, not a condition. The term refers to pain that travels along the distribution of the sciatic nerve, but it tells us nothing about the underlying issue that creates these symptoms. The radiating pain, numbness, or tingling that shoots from the lower back through the gluteal region and down the leg may originate from a herniated disc, muscular entrapment, postural imbalance, or joint dysfunction.

In this column, we explore the primary issues that lead to sciatic-type symptoms, how to differentiate between them in clinical practice, and the role of massage therapy in addressing many of the contributing soft-tissue factors.

Anatomy and Causes of Pain

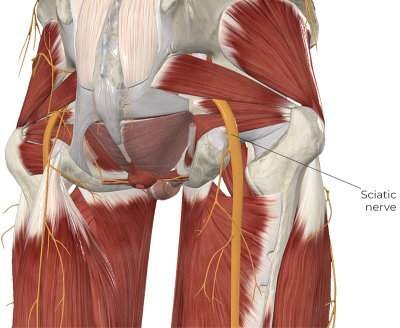

The sciatic nerve is the largest (about the width of your little finger) and longest nerve in the human body. These nerves branch from L4, L5, S1, S2, and S3 on each side, forming a substantial neural pathway that originates from the lumbosacral plexus. The nerve exits the pelvis through the greater sciatic foramen and then courses through the gluteal region adjacent to the piriformis muscle (Image 1). It then continues down the posterior thigh before branching into the tibial and common fibular (peroneal) nerves, terminating in the foot.

Several key structures along its path may compress or irritate the nerve. Additionally, its superficial course through the gluteal region makes it particularly susceptible to compression and tension pathologies in several locations. Common sites of sciatic nerve impingement include the intervertebral foramina, adjacent to the greater sciatic foramen, against the piriformis muscle, and between the piriformis and sacrospinous ligament (Image 1).

The nerve is also susceptible to adverse neural tension in the hamstring region, where symptoms can sometimes be mistaken for a hamstring injury. Additionally, other factors such as inflammation or myofascial trigger points in the gluteal muscles can also produce sciatic-like symptoms. Evaluating the tissues involved as accurately as possible before applying any treatments is the key to efficiently resolving your clients’ pain.

Common Causes of Sciatic Pain

Lumbar Nerve Root Pathology

Lumbar nerve roots can be compressed by protruding discs, spinal tumors, narrowing of the intervertebral foramen (stenosis), or bone spurs in the region. Disc compression is the most common of these. The largest percentage of disc herniations occurs at the L4/L5 or L5/S1 disc spaces. Disc herniation occurs when compressive forces push the inner portion of the disc (nucleus pulposus) through the outer disc border (annulus fibrosus), creating pressure on adjacent nerve roots. Ironically, some people with disc herniations have no back discomfort, and herniations can resolve spontaneously. Consequently, the presence of a disc herniation does not mandate that it will produce symptoms.

Another key challenge at the nerve root level is chemical irritation, such as that from local inflammation. There is also a neurotoxic enzyme called phospholipase A2 (PLA2), which may leak out of the intervertebral disc and contact the nerve roots, causing sciatic pain.1 The issue of pain due to chemical irritation is important because imaging studies like X-ray or MRI may suggest nothing is pressing on the nerve. Yet the pain remains, just not mechanical in nature.

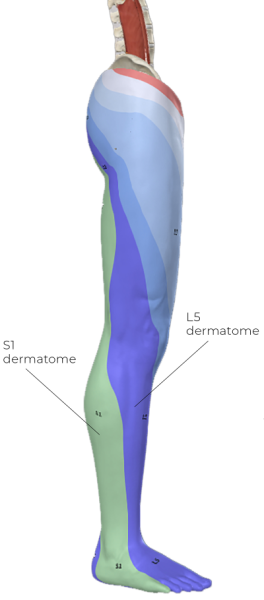

Clinical signs of nerve root involvement include pain or neurological symptoms in a particular dermatome. The dermatome is an area of skin innervated by a specific nerve root (Image 2).

However, dermatomal symptom evaluation has a significant degree of variability, so it is not considered highly accurate. Other assessments include special orthopedic tests such as the straight leg raise (SLR) test (Image 3). The SLR applies progressive levels of stretch to the sciatic nerve to assess the reproduction of symptoms. The SLR test is not a perfect evaluation, but it has relatively good reliability and is used frequently.

No evaluation procedure should be used in a vacuum. Your assessment should include additional information, such as a history and other physical assessments, to provide a comprehensive picture that may indicate potential nerve root involvement.

Piriformis Syndrome

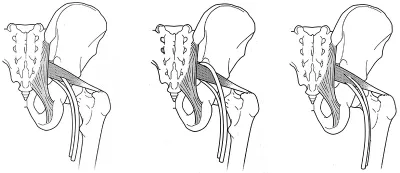

Piriformis syndrome involves irritation of the sciatic nerve, located deep within the gluteal space. Divisions of the nerve can pass above, below, or through the piriformis muscle (Image 4). Symptoms can closely mimic nerve root pathology (radiculopathy). Interestingly, neurological symptoms are not strongly correlated with the nerve’s passage through the piriformis. Consequently, anatomical variations alone do not explain the condition.

Despite the potential for sciatic nerve compression in this area, the idea of piriformis syndrome remains controversial. Research has yet to produce consistent figures on the frequency of this condition.2 One of the key challenges is the lack of a gold standard for evaluating the condition. Diagnostic studies can show the location of the nerve or its divisions in relation to the piriformis. Still, they cannot confirm whether the muscle is directly causing specific symptoms (a complaint that could be leveled at many diagnostic tests). Contributing factors to this condition include prolonged sitting, poor postural mechanics, direct trauma to the buttocks, and muscle imbalances affecting hip stability.

Other Suspect Conditions

Several additional conditions can create sciatic-like symptoms through different mechanisms. Neural tension of the sciatic nerve is an often overlooked contributor to pain in this region and involves excess pulling forces on the nerve. For example, when scar tissue forms in the repair of a hamstring strain in the posterior thigh, it can tether the sciatic nerve to local hamstring fibers. Such restrictions make the nerve less able to glide along adjacent tissues. The result is excess pulling stress, or neural tension, on the nerve during its movement.

Inflammation due to a ligament sprain, particularly of the iliolumbar ligament, can irritate the nearby lumbar nerve roots, causing sciatic-type symptoms. Scoliosis and spinal instability can alter normal biomechanics, creating intermittent nerve compression with movement. And, the anterior slippage of one vertebra on another (spondylolisthesis) can cause movement-related nerve root impingement as they exit the intervertebral foramina.

Referred pain from myofascial trigger points can mimic neural symptoms, though careful assessment usually reveals different patterns. Trigger points in the gluteus minimus, for example, can refer pain down the posterior or lateral leg in patterns that superficially resemble L5 radiculopathy. However, trigger-point referral lacks the neurological signs associated with true nerve root compression. Additionally, if you can reproduce the symptoms by applying pressure to the hip abductor muscles, it is more likely to indicate trigger-point referral rather than nerve irritation.

Red Flag Considerations

Sciatic symptoms can sometimes indicate a serious pathology that requires immediate medical referral. Cauda equina syndrome represents a critical emergency, because it is a condition in which a disc presses directly posterior on the spinal cord. Symptoms include pain, weakness, numbness, and/or tingling in the groin, genital region, and/or both legs. There may also be loss of bowel and/or bladder control. This condition requires emergency medical intervention to prevent permanent neurological damage.

Additional red flags include progressive neurological deficits, particularly foot drop or significant muscle weakness, bilateral leg symptoms, pelvic floor numbness, and systemic signs like fever or unexplained weight loss. Night pain that disrupts sleep or pain that continues to worsen despite conservative treatment also warrants medical evaluation.

Understanding these warning signs enables massage therapists to provide appropriate care while maintaining professional boundaries. Early recognition and prompt referral can prevent serious complications.

Suggested Treatment Approaches

Working with neural conditions requires a different strategy than the usual focus on deeper techniques for reducing muscle tightness. Aggressive techniques that increase neural symptoms are counterproductive and may worsen the condition. Instead, focus on addressing contributing muscular and fascial dysfunctions that create mechanical stress on neural pathways. This approach may involve both broad and general strokes as well as more localized and targeted treatments in other areas.

Neural symptoms often result from mechanical compression or tension created by dysfunctional soft tissues.

Remember that massage doesn’t directly treat the nerve itself but rather influences the surrounding tissues that affect neural function. This indirect approach proves effective because neural symptoms often result from mechanical compression or tension created by dysfunctional soft tissues.

Gluteal Muscles

These muscles are often a good starting point for clients with sciatic symptoms. Always begin with broad pressure strokes, using palms or forearms, to initially address general tension patterns. Progress to more specific work using knuckles, fingertips, or pressure tools for trigger-point work, but apply gentle pressure. The small contact surface treatments are most effective after superficial layers have been relaxed—and far less painful.

When working the gluteals, it’s usually more effective to use sustained pressure techniques rather than aggressive friction or rapid pressure techniques to avoid increasing protective muscle guarding. Treating the piriformis is important, but it poses significant challenges due to the muscle’s depth. Additionally, applying direct pressure to a muscle that is compressing a nerve can aggravate symptoms; stop if treatment produces those symptoms.

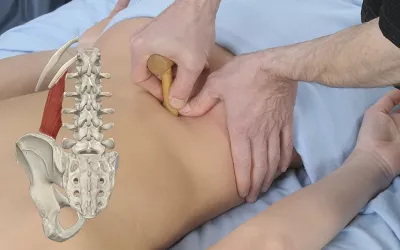

Active engagement techniques are a great tool to use when working the piriformis because they increase the muscle’s density deep to the gluteus maximus and make your pressure applications more effective. Perform these treatments with the client in a prone position, applying pressure to the piriformis either with static compression or a short stripping technique while the muscle is contracting eccentrically (Image 5). In this image, the therapist is pulling in the direction of the black arrow and the client is attempting to pull in the opposite direction but slowly letting go so the therapist can gradually move the hip into medial rotation. This stretches the piriformis and works it during its eccentric contraction for a very effective approach.

Quadratus Lumborum and Paraspinals

These muscles contribute significantly to lumbar dysfunction but require a careful approach due to their depth. While nerve root compression is a key component of many sciatic symptoms, massage treatment is not specifically intended to address the nerve itself. Instead, the goal is to reduce hypertonicity in the stabilizing muscles of the spine, restore biomechanical balance, and settle local nervous system inputs that may further aggravate the condition.

Broad contact approaches, such as palm or forearm gliding, will reduce hypertonicity in these low back muscles. Be cautious in the lumbar region that your pressure does not perpetuate neurological symptoms. After initial work with broad-based contact, you can use small contact surface treatments, such as the thumb, fingertips, elbow, or pressure tools, to apply more specific and focused pressure on these muscles.

It’s challenging to work on the deepest muscles, such as the quadratus lumborum, with small contact surface pressure, so be aware of your anatomical landmarks (Image 6). For the quadratus lumborum, pay attention to depth and angle of pressure to make sure you do not press against the tips of the transverse processes. The nerve roots are located anterior to the transverse processes, so you’re unlikely to press directly on them. However, pressure on the low-back region can cause minor degrees of vertebral movement, which may aggravate neurological symptoms.

With any of these treatments, it’s critical to frequently check in with your client about pressure levels and to confirm your work is not reproducing any neurological symptoms.

When to Refer

Having clear guidelines for referrals protects both you and your clients and ensures appropriate care. Refer the client when symptoms fail to improve within 3–4 massage sessions, particularly if objective measures, such as range of motion or pain levels, remain unchanged. Also, if symptoms progressively get worse, refer the client to another health-care professional. Neurological signs, including muscle weakness, sensory changes, or alterations in reflexes, require a physician’s assessment. These findings may indicate significant nerve compromise needing medical intervention. Document these findings carefully and communicate them clearly in referral communications.

The onset of bowel or bladder symptoms, saddle anesthesia (pelvic floor numbness), or bilateral leg involvement represents a medical emergency requiring immediate referral. Do not delay referral for these serious presentations, as early intervention can prevent permanent neurological damage.

Conclusion and Takeaways

Sciatic pain challenges massage therapists to think beyond simple symptom treatment toward comprehensive condition management. Understanding that sciatica represents a symptom rather than a specific condition fundamentally changes treatment approaches. Each underlying cause—whether disc herniation, piriformis syndrome, or an inflammatory cause—requires specific assessment and intervention strategies. Careful assessment helps differentiate between various causes of sciatic symptoms and guides treatment selection and referral decisions.

Clinical reasoning forms the foundation of effective treatment. Massage therapy offers a valuable intervention for many causes of sciatic symptoms, but success depends on the appropriate application based on sound reasoning. Effective treatment for sciatica pain often requires a comprehensive approach, providing condition-specific and tailored care that addresses not only the primary symptoms but also the contributing factors. Massage plays a highly beneficial role in addressing this often chronic form of pain in the rear.

Notes

1. Muriel Piperno et al., “Phospholipase A2 Activity in Herniated Lumbar Discs: Clinical Correlations and Inhibition by Piroxicam,” Spine 22, no. 18 (September 1997): 2061–5, https://doi.org/10.1097/00007632-199709150-00001.

2. Damla Yürük et al., “Prevalence of Piriformis Syndrome in Sciatica Patients: Predictability of Specific Tests and Radiological Findings for Diagnosis,” British Journal of Pain 18, no. 5 (May 2024): 418–24, https://doi.org/10.1177/20494637241254349.